Digital wallets and the “only Apple Pay does this” mythology

Apple Pay is great, but I think there is some misunderstanding out there about the details of how it works.

John Gruber has some choice words for Merrick Garland and crew, but this paragraph stood out as uniquely interesting to me:

Apple Pay through Wallet obfuscates your actual credit card numbers, which retailers infamously use to track customers. It’s far more private than using your credit card itself. I highly doubt any banks or credit card issuers would do this themselves if given access to NFC tap-to-pay.

Payments you say? My specialty!

First off, this obfuscation is referring to the DPAN, which is distinct from the FPAN.

Ahem, sorry for the jargon, but it's important to understand what's happening, so let me explain.

The FPAN is the “funding primary account number” and it’s the 15-18 digit number printed on your physical card. The DPAN is your “device primary account number”.

Think of the DPAN as something like DNS records. When you type “birchtree.me” into your browser, your browser is able to determine what IP address this domain is related to and directs you there. I can keep my website physically in the same place on the same IP address, but I can change the domain to birchtree.com or wigglewobble.org and browsers will know what to do without the user needing to know what IP address is involved.

This might be the nerdiest way to explain DPANs, but I know my audience, so I think this may have helped at least some of you. Your same card used through Apple Pay on your iPhone and iPad will show different DPANs, though since each device gets its own number.

It’s notable that it’s called a DPAN and not “the Apple Pay number” – it’s a generic term, and that’s because this is a standard feature of digital wallets everywhere, not just Apple Pay. Google Pay and Samsung Pay are the biggest other digital wallets in the U.S. and they both do exactly the same thing. While it’s not technically using a DPAN since the payment runs through different companies, Amazon Pay and Shop Pay buttons also obscure the actual FPAN (full card number) from merchants.

I feel like this comes up a lot, but I can not stress enough to you how little merchants want to ever ever ever handle your actual credit card number. It adds so much risk on their end and modern payment acceptance tools make it easy to collect payment details in a way that makes sure as few people as possible have access to the real card info.

Gruber mentions banks absolutely not wanting to use DPANs themselves, but we actually don’t need to speculate about this, we have this info already. Numerous banks from Walls Fargo to Chase to Bank of America have (or had) digital wallets, all of which used DPANs to protect your plain text account number. Paze is what a few big U.S. banks use today and it of course uses DPANs as well. In fact the top reason they give for why you should use Paze is, “Paze does not share your actual card number with the merchant.”

On tracking customers

Then there’s the issue of the DPAN changing over every transaction, which wasn’t called out by Gruber, but I see people floating around. This is not really true, though.

A previous version of this post suggested the DPAN changes between merchants, but that was a mistake. Serves me right for cranking this post out too quickly. Seriously, my bad.

The DPAN is always the same for subsequent transactions at the same merchant. So yes, while this can hinder data brokers from easily buying transaction data from a bunch of different merchants and figuring out shopping trends across those merchants, it does nothing to stop a single merchant from seeing your transaction history with just the DPAN provided by Apple Pay. If that Target story from forever ago about Target knowing a teen was pregnant based on their Target purchase history, Apple Pay doesn’t stop someone like Target from being able to track that. And yes, it’s the same with the other digital wallets out there.

A final thing to note about DPANs is that they are much better for you as a customer in the event of a data breach. No merchant should be handling your credit card number directly in 2024, but let’s say the payment gateway gets hacked and leaks the DPAN and expiration date for a transaction you ran at a shop. In that case, the attacker wouldn’t be able to do anything with your DPAN they acquired because DPANs only work when submitted as a part of an encrypted bundle that’s unique to each transaction. There is a way to run recurring transactions on a card collected via Apple Pay, but that should not be possible for a hacker and now we’re a bit in the weeds, so let’s just say that your FPAN being in a data breach is way worse than your DPAN which is collected by all digital wallets.

Personal info in Apple Pay

There’s also an idea I see sometimes (again, not in Gruber’s linked post, but that I want to clear up anyway) that Apple Pay obscures your personal information. That’s simply not true.

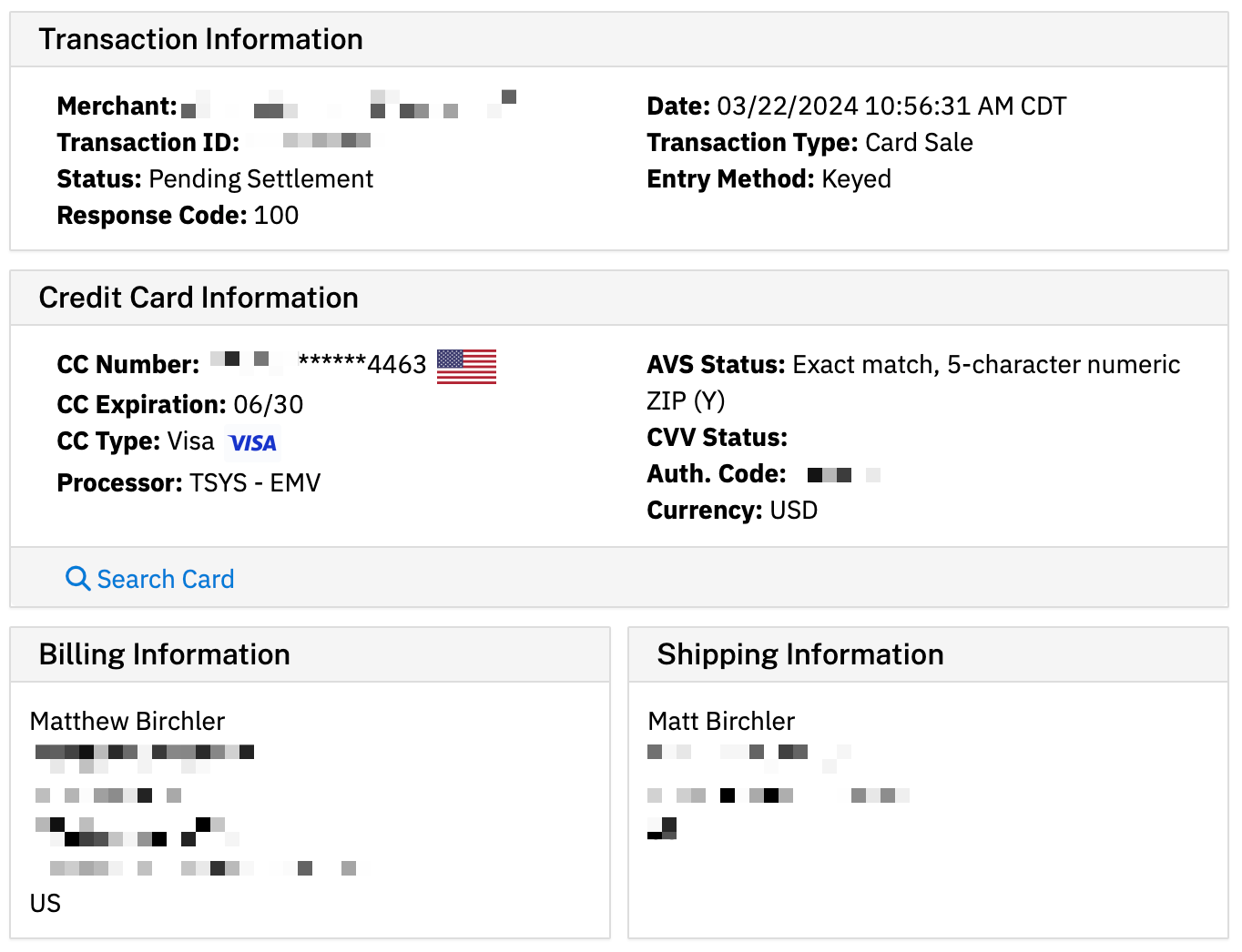

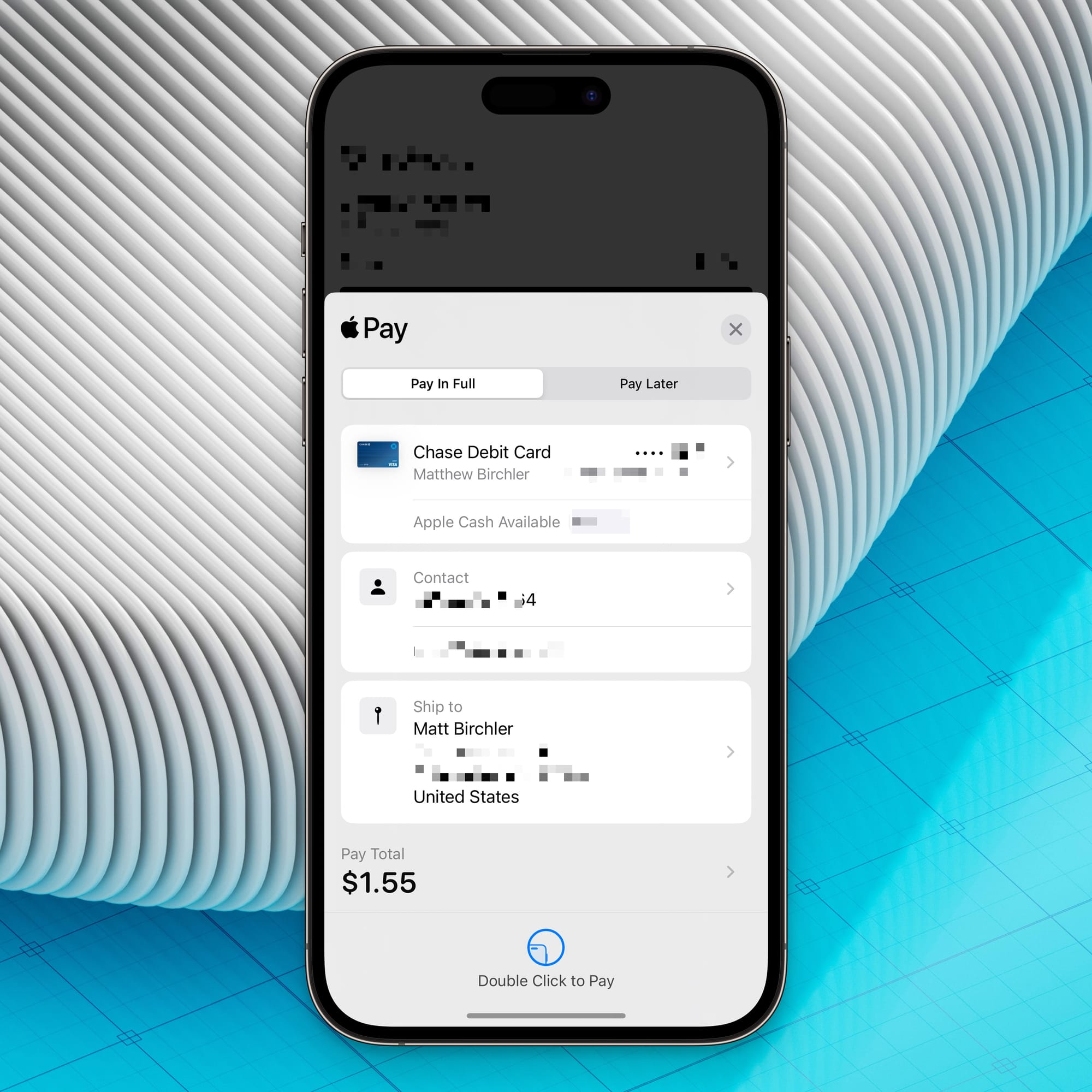

Because I’m a very dedicated blogger, I actually ran a real Apple Pay transaction on one of my test merchant accounts (but that run very real transactions) and looked at the merchant-level reporting for it. Here’s what I see as the merchant for this Apple Pay transaction:

I’ve blurred out a good amount of it because that’s my real billing and home address as well as my full name and email address.

And if you think about it, of course that info would be there! In this example, my checkout page was for a physical item so I needed the customer’s shipping info. Apple Pay’s SDK allows me to choose what personal info I want to get from the customer, and it’s for this exact sort of situation.

Oh, and product info can be passed into Apple Pay to show you what you’re buying, and that info is sent to the merchant as well. Again, of course it is since the merchant needs to know what you bought.

Basically, when that Apple Pay card pops up when you’re checking out, expect everything on that card to be sent to the merchant. In that way it’s just like all other payment forms; the merchant chooses how much personal info they want or need to collect, and Apple Pay doesn’t prevent them from asking you for that at checkout.

And yes, this is how other digital wallets work.

Takeaway

I hope what you take away from this post is that while Apple Pay is a great way to pay for things and that Apple did a great job mainstreaming digital wallets like this, what they do is not unique in the industry. DPANs are great for making it harder to track one person’s purchases across multiple merchants and they make customers less at risk in the event of a data breach of payment card info.

None of us can know everything about everything, and I don’t think it’s reasonable to expect everyone to know about all the details of how digital wallets work. That’s why I find opportunities like this to be so useful; I can share more info than most in this Apple niche, and I hope it’s informative.